Glory Years of Royal Capital of Arakan

The Glory Years of Royal Capital of Arakan was witnessed by Fr Sebastio Manrique, born in Portugal in 1590. He joined the order of Saint Augustine and traveled throughout the far east and Asia as a missionary. He was appointed as an emissary of the viceroy of Portuguese India to Arakan from 1629 – 1635.

His writings reflect his fascination with the customs of the royal court, the people, and the different religions practiced in Arakan during this time.

Manrique spent around sixteen years from 1628 – 1643 AD traveling throughout the far east and Asia, he returned to Goa which was the base for the order of Saint Augustine in India, and whilst there he had the desire to travel to Japan to continue his missionary work, but Japan was closed to foreigners, especially to those preaching Christianity, and no ship would take him there, so he returned to India and from there set out for Europe by land.

He left India in 1641 arriving in Rome in 1643, his travels took him through Persia, Pakistan, Iraq, Malta, Cyprus, and eventually Rome where he wrote his memoir “Itinerary of the Oriental Missions of Father Manrique” in Spanish. Missiones Orientales del P. Manrique and translated into English by the Hakluyt Society of London under the joint editorship of Luard and Hestern in 1926-27).

Manrique’s Description of the Royal Capital of Arakan (Mrauk-U)

In the English version of his writings translated from Spanish, he refers to Arakan as Arracao. His description of the royal city describes it as being built in a beautiful valley, about fifteen leagues in circuit, and surrounded by the Arakan Yoma Mountains which acted as a natural fortification, isolating the region from the rest of Burma making it unnecessary to build man-made fortifications, however, it was accessible via the Bay of Bengal and the Indian subcontinent.

According to Manrique’s reference to Arakan’s fortification, he mentions that “On the inside, these mountains had been leveled in necessary parts with rammers, and where they have been cut through from top to bottom, gates had been erected for going in and out, whilst above them are some bulwarks provided with artillery so that the city would naturally be impregnable as if it belonged to another more warlike nation”.

He described the middle of the city as “having a large and copious river that branches off through various parts, making the greater number of its streets navigable for different kinds of craft, big and small, the vehicular service, virtually an independent Kingdom, with King Thiri Thudhammaraza on the throne”. (also known as Min Hari and Salim Shah II).

NOTE: (the principal river systems in the region were the Naf Estuary which shares a border between Bangladesh and Burma, the Mayu river named after nearby Mayu Mountain, formerly known as Manayuwaddy River, the Kaladan River which forms the border between Burma and India, and the Lemro River valleys formerly known as Aizannadi River which flows into the Bay of Bengal east of Sittwe).

Manrique describes the estuaries along these rivers as vibrant with merchants selling all manner of fresh produce, meat, fish, spices, both salted and dried as well as household commodities.

He describes the river as “entering the sea in two places first, at the harbour of Oriatan; and secondly, on the side of the Dobazi, where merchants of different nations lived, the greater number of Maumetans (Mohammedans/Muslims), with their captains also belonging to that sect. At the high tide the sea enters the town with great violence by seven gates and at the low tide runs off with equal force”.

Manrique’s description of the Royal palaces

“The Royal palaces are also constructed with the same arundinaceous materials, and they have massive wooden columns of such extraordinary length and straightness that one wonders if there are trees so tall and so straight. These places contain also some rooms made of odoriferous woods, such as white and red sandalwood, and wild or forest eaglewood, so those rooms thus gratify the sense of smell with their own natural fragrance.

Within this palace the hall is gilded from top to bottom, it is referred to as the golden House because it was decorated with a vine of the purest gold which occupied the whole roof of the hall, with a hundred and odd combalengas of the same pure gold. These combalengas are in breadth and shaped like big pumpkins (Calabasas) of the kind we call Guinea pumpkins, and they say that each one of them weighs ten bissas (viss), or forty pounds in Spanish”.

Manrique’s reference to seven gold hollow idols

“Each with the proportions and size of a man, and is two inches (dados) thick. He could not ascertain the weight of each of these idols, on account of the various estimates given by those whom he questioned. Those idols are adorned on the forehead, breast, arms, and waist with many fine precious stones, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, as well as some brilliant old Rock diamonds, of more than ordinary size.

In the same golden hall stood eight pitchers (cantaros) of gold each four palms high, seven-inch circumference, and one inch thick. There were also nine dishes of the same metal, each three palms high thirteen inches in circumference, and one inch thick. This grand and very rich hall contain still those equally ancient and most celebrated precious Chaneguas of the Tangu (Taungou), the prime cause, past, and present, of so many wars and so much bloodshed on the part of various nations, such as the Siammes (Siamese), the Pegus, Tangus, Bramas, Avvas (Ava), Sions, (Siones) (Shans), and now at present the Mogos and Mogars”.

NOTE: in the book “The mons” written by Emmanuel Guillon in the English translation it refers to Manrique’s description of the Chaneguas as follows:

“Although Manrqiques writings referred to the Arakanese Kingdom, they also applied to the mons in more than one aspect regarding the Cheneguas which was the instigator of numerous wars between the Mons, Thais, Shan, Arakanese, and Burmese over the two enormous rubies which were set in a golden chain to make two ear pendants which were used only at the coronation of the kings”.

NOTE: Between the 15th – 16th centuries the infiltration of Muslims from Bengalto Arakan took place. This constituted the start of the history of Arakan with two distinct groups of people – the Burmese Rakhines and the Muslim Rohingya.

Information source referring to the Chanequas “A Guide to Mrauk-U” written by Thun Shwe Khine:

King Min Razagyi (ruling Arakan from 1593-1612 AD) attacked King Nanda Bayin ruler of the Toungoo Dynasty (ruling 1581-99) in alliance with the Prince of Toungoo Nanda Bayins’s brother) they besieged Pegu and took Nanda Bayin prisoner resulting in the dismemberment of the Bayinnaung’s empire.

Manrique says the Rakhine and Portuguese sacked Toungoo after the fall of Bago and brought away the Kyauknagats (Chaneguas) from Toungoo. But history disagrees with him about the raid of Toungoo.

Manriques description of the Chaneguas:

“This unique treasure is contained in a casket of gold, two palms long and proportionately broad, the whole of it is covered with very artistic boughs, flowers, and birds, and within this tracery are encased very fine diamonds, rubies, and pearls of extraordinary greatness. This admirable casket stands in the centre of the hall on a square table of gold, three palms long; this table is elaborately engraved and set with many rich gems. To stimulate more human cupidity, it is covered with a cloth of white satin, entirely embroidered with gold and pearls of ordinary size”.

Manrique freely confesses that, although he had seen in other parts of the East many things of great price and value he said, “Yet, when they opened the casket for me, and I beheld the chaneguas, I stood amazed, especially on seeing that I could scarcely fix my eyes on them, due to the rutilant splendor they cast. These Chaneguas are two rubies shaped like an obelisk and pyramid, of the length (altura) of the small finger, and the bottom of each has the circumference of a small hen’s egg. These most precious jewels are used only at the coronation of the Mogo Kings, or in their greatest solemnities”.

Manrique describes chaneguas as a pendant, or earring, an article worn at the ears both by the Mogos, the Peguans, and Bramas; for this purpose, they pierce their ears when young, and put in them something heavy, which keeps stretching and enlarging them until they reach almost the shoulders. he also goes on to say that “In one of the inner courts of that palace, there is also a statue of King Braka, tyrant of the Empire of Pegu, who was slain by a Pegu lord called Xeni Decatam (Shmin Sawhtut, a Bago nobleman), whom he had ordered to be killed”.

NOTE:

In Manrique’s writing mentioning King Braka the tyrant of Pegu, this is likely referring to Filipe de Brito, an adventurer born in Lisbon in 1566 who declared independence, after capturing the crown prince of Arakan, taking him hostage, then marrying the daughter of the ruler of Martaban and became nominally a subject of Siam. De Brito went to Goa in 1600 and had himself awarded the titles of “Commander of Syriam”, “General of the conquests of Pegu”, and “King of Pegu” by the Portuguese royal court.

Manrique said “While quartering at a small country house (villa town), in some houses belonging to a Verela, or Ido temple (likely a church), with four thousand Brahmans, this Brahma (Burmese) King was waiting for the rest of his army which he had ordered to collect, with the intention of marching against a prince who had revolted in Martavan (Martaban). Now, one night, Xemi Decatam with six hundred Peguan fell unexpectedly on (King Braka) at the houses of the Vaakto. Luck would have it that they found the Tyrant busy in a closet, for he was suffering at the time from a flux of the belly, and they killed him”.

NOTE:

The port city of Syriam, today known as Thanlyin located across Bago River with a bridge linked to the city of Yangon fell to Burmese forces in April 1613. Given that de Brito was said to have forced the locals to convert to Catholicism and to have desecrated Buddhist temples (such as removing a major bell from the historical Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon), he was executed by impalement.

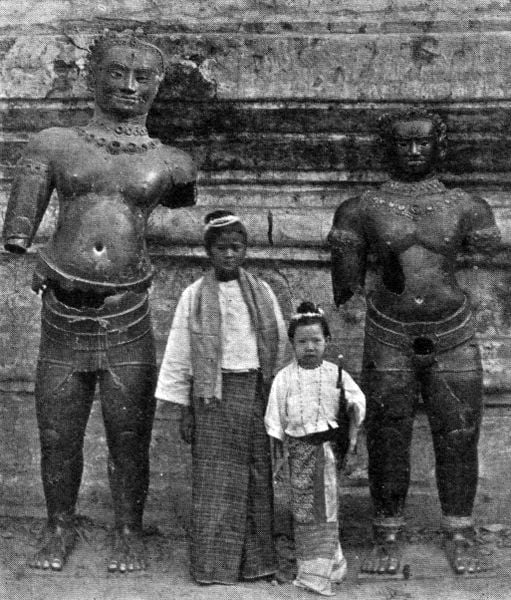

According to Manrique’s account, “The Burmans at that time held Xeni Decatam as a Saint, and as such, they dedicated a temple to him, because he had so greatly aggrandized and exalted their nation, and, to perpetuate his memory forever, they resolved to make an image of him, so, they made a bronze figure and seated it on a table, also of metal, and around him are sundry monsters in bronze of surprising size. The most wonderful are four giants of both sexes, each of them sixteen palms high and holding maces in their hands: a monstrous brood. With them, there is another monster of the same material, half elephant, half bull, eleven palms high, another horrid-looking object. Still other animals, also of bronze from the port of that cortage; but as they are one of ordinary shape and size”.

Manrique’s description of the statues

“The statues of the four Giants were, they say, adorned with many precious stones, and in the places where they were encased, there are still traces, of them. That statue is venerated by many of those Gentiles, who come to see it, and out of devotion anoint it with sandal and fragrant oils. And when 39 people are afflicted with diarrhoea, they came to him as to their advocate against that infirmity, bringing vases full of water, they bathe him, and the water which flows out, after passing through his body, is collected and given to drink to those who suffer from the illness”.

“At a small distance from that Royal Palace, there is a lake, the water of which is dammed off, and they say it is more than thirty leagues long. The lake is divided into several arms, containing many islets, quite cool, and planted with fruit-bearing trees. The greater number of these islets (islands) are inhabited by Raulins. Some of these live in Varelas, some of their Varlas being built like our Convents. Others live in private houses. I shall give a special account of them all when I describe the warship of those nations”.

“On that big lake, there are many boats, but they do not communicate with the interior of the city, as the passage is dammed up. Their ancient histories say that this lake was opened and begun when that Kingdom separated and made itself independent from the Empire of Pegu, the purpose of it is this. In case they should be besieged, they would retire to the suburbs contiguous to the Lake, and, as a last resource, let the waters escape, and the violence of the onrush would be such that they would inundate the city and at the same time destroy the enemy. It is for this reason that they still keep these waters”.

Manrique’s description of the population of the area:

“To go back to the thread of our history, I say that the city of Arracan must have, according to the common estimate, one hundred and sixty thousand inhabitants, exclusive of foreign merchants, who are very numerous, as the place is a very important roadstead for vessels coming there from Bengala, Mussulapantan, Tanaussarim, Martavan, Achem, and Jacalara (Batavia): there are, besides, other foreigners, both merchants and soldiers who are fixed there and in the King’s pay, as I have said: these are Portuguese, Pegus, Bramas, and Mogors (Muslim, Indian). In addition to these, there are also many Christians, Japons, Bengalas, and of other nations”.

The Kingdom of Arracan is limited on the south by the Kingdom of Pegu from which it is divided by the high mountains of the Pre (Yoma), on the other side, it borders the Kingdom of Bengals through the Kingdom of Chatigan, whence the coastline runs up to the Kingdom of Chudube, and Cape Negrais. The whole of that coast is very wild; and, though it has some harbours and islets, these are very unsafe, owing to certain winds blowing there, which are dangerous to some vessels.

Referenced: The Hidden City of Myanmar | Travel | Smithsonian Magazine

Those glory days ended in 1784 when Burmese invaders crossed the range of hills dividing their kingdom from Arakan and conquered Mrauk U after several months. The soldiers marched the king and his family, with other members of the elite, into captivity. Mrauk U was left to moulder. The British, who seized Arakan in the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824, had developed an interest in Burmese archaeology during the Victorian era and supported the local restoration of the Shitthaung temple in the late 1800s. But World War II and its aftermath derailed those efforts, and successive Burmese military regimes cut off the country from the rest of the world. Through most of Myanmar’s independence, “the city attracted zero interest” from historians or preservationists, says Leider, who heads the École Française d’Extrême-Orient in Yangon.

About the giant bronze statues mentioned in Manrique’s writing

The above and the following information were referenced in the book “A Guide to Mrauk-U” written by Thun Shwe Khine:

The statues originally stood as guardians in Cambodia’s Angkor Wat. They were among 30 statues taken by the Thai in 1431 AD. In 1564 the Myanmar King Bayin Naung Won Ayutthia carried the statues away to Bago. According to the Rakhine history, King Min Razagyi of Mrauk-u conquered Bago in 1599 ad and carried away to this capital of Mrauk-u not only the treasures including these statues from Ayutthia but also his rival Kings daughter and a white elephant. In 1784 Dodawparas forces took back the surviving statues to Amarapura.

OUR NOTES REGARDING THE BRONZE STATUES MENTIONED ABOVE :

The last time we saw these statues was In 2014 they were housed in the Mahamuni Pagoda in Mandalay, they were renovating and reconstructing an area to house the statues.

Footnote: Father Manrique was murdered in 1669 in London by his Portuguese servant.

Other references: Fr. Manrique in Arakan during the reign of King Thiri Thudhamma